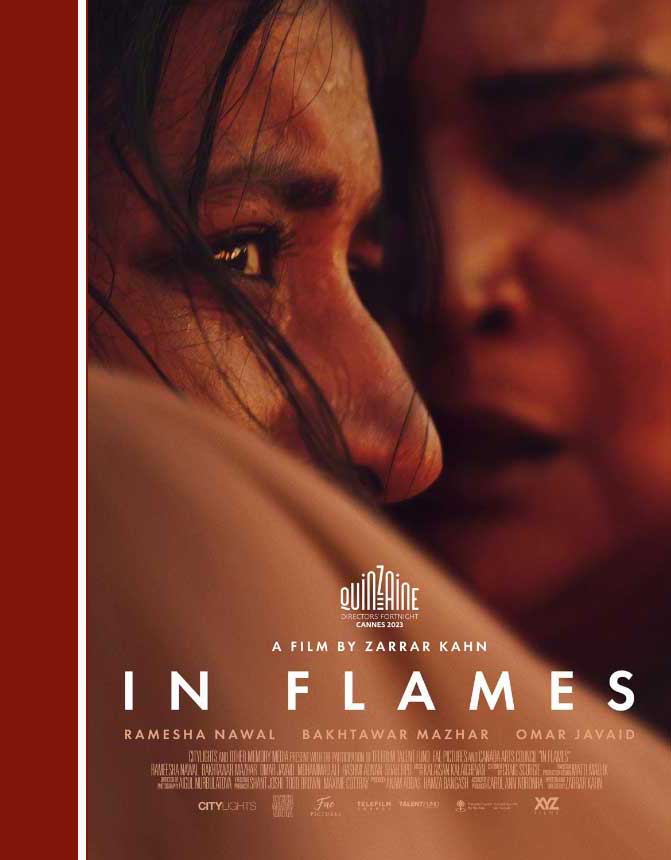

In Flames

Zarrar Kahn’s In Flames made waves at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival’s sidebar, Directors’ Fortnight with its multi-genre take on horror, trauma, patriarchy and the supernatural. With an ambiguous treatment of which direction the Pakistani film wants to go, it starts off as a slice-of-life, lighthearted watch as the lead character, Mariam does her best to follow her dream of becoming a doctor in a hardcore patriarchal society.

Lopa K

M.A. Lit. (English) | passed, 2021

Following the death of her grandfather, Mariam does her best to protect her mother, Fariha from her greedy grand uncle Nasir who has an eye on their property. One day, while driving to the library to study, a man attacks her. Shaken by the experience and frustrated by her friend, Rabiya’s suggestion to let it go, she finds solace in the new boy in town, Asad. As he tries to help her, they end up falling for each other with him courting her. Amidst it all, Mariam cannot help but get the feeling that she is being stalked by multiple, strange men. It gets worse when a beach date goes wrong and Asad and Mariam get into an accident.

In Flames flexes the rich South Asian culture unlike the usual poverty porn that we get in indie films (Western directors exoticizing the slums and street vendors while the heroes go about their mission, take notes). We then have the Urdu-English speech making it relatable for all desi people. It also sheds some much needed light on these countries and how there has been some progress when it comes to freedom from the age-old oppressive rules. Many women like Rabiya and Fariha can choose whether to wear a hijab or not, women drive, study and pursue their careers.

Symbolisms go into overdrive in In Flames as viewers try to put the pieces together—Is it all happening in Mariam’s head or is there something sinister afoot?

Back to the plot, the budding relationship of Asad and Mariam is cute as he tries to woo her and she pretends to keep him at a distance but likes him as well. But underneath the scenic segments with beautiful cinematography, an underlying danger remains till it rises to the forefront and makes Mariam question reality and herself. This dichotomy of the light, cheerful music, the adorableness of the couple and the slow panning, neon lights and creeping music with strange men makes us wonder if we are watching a realist melodrama or a horror story.

With a twist to the noir aesthetic, the play of light and shadows, locations with multiple entrances and paranormal hints, the symbolisms go into overdrive as viewers try to put the pieces together — is it all happening in Mariam’s head or is there something sinister afoot? The scene where the family is seen through a mirror adds to the idea that they are removed from her, no one can understand Mariam’s troubles. Her double reflection in the mirror (Kahn’s favourite metaphor) represents the duality of the different themes of In Flames such as PTSD vs ghosts or oppression vs empowerment.

But maybe it is this experimentation that reduces the ending’s impact. Surreal scenes like the characters teleporting to a different place, the random men Mariam sees apart from her father and Asad all feels odd. Her hauntings may be out of guilt or by vengeful spirits. But as we wait for an explanation for the hauntings, it takes away our focus from the plot.

As for Mariam’s makeup, at one point while we appreciate the realist look of her gaunt and haunted eyes, the clumpy mascara after she is recovering from her asthma attack seems like a mistake rather than an artistic choice.

Well, for the sake of the strong first half, it makes viewers sit through the end. But maybe In Flames would have been better as a psychological thriller as it fails the very first prerequisite of being a supernatural horror film – it’s not scary enough. But questioning Mariam’s psyche, that is what keeps us hooked.

Share Widely